Responding to the Kivu Ebola Epidemic (2018-2020)

Moving Forward with Lessons Learned

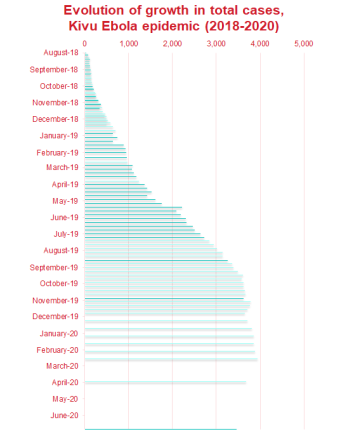

It’s been a little more than a year since the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) declared the end of the tenth, most deadly, and largest Ebola outbreak in DRC. The outbreak started on 1 August 2018 and lasted for nearly two years. In that time, the epidemic infected 3,470 people and resulted in 2,280 deaths, with a staggering 66% death rate across the provinces of North Kivu, Ituri and South Kivu in Eastern DRC. Following the first widespread use of an Ebola vaccine, which reached more than 300,000 people, the outbreak was eventually contained and declared over on 25 June 2020.

Mercy Corps played an important role in the response to the tenth Ebola epidemic, led by the Ministry of Health and the World Health Organisation (WHO), helping to turn the tide against the disease through supporting affected communities to prevent its spread and begin the process of rebuilding their lives.

The legacy of the tenth outbreak lives on, however, with DRC since suffering two additional outbreaks of the disease: one in the western province of Equateur in 2020 and another in 2021 in the same areas affected by the tenth outbreak, believed to be linked to the earlier epidemic. Although both outbreaks were declared over within a few months, the threat of a resurgence lingers.

Meanwhile, DRC continues to be affected by the global COVID pandemic, which poses similar challenges to the country’s community health structures, and compounds long standing challenges of violence and armed conflict, poverty, food insecurity and unemployment.

What we learned from the response remains as relevant as ever, therefore, in helping to show how humanitarian assistance can best support a way forward for communities in Eastern DRC.

Here we present what we did, what we learned, and what needs to happen next.

How Mercy Corps Assisted the Response

While not a specialist health organization, Mercy Corps became involved in the response early on, leveraging our work on water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) in urban areas and our experience working with communities in rural North Kivu to support two key pillars of the response: infection prevention and control (IPC), and risk communication and community engagement (RCCE).

Through the course of the epidemic Mercy Corps ultimately implemented nine distinct projects, with funding from donors including the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), the United Nations Children’s Fun (UNICEF), the United Nations’ DRC Humanitarian Fund and Mercy Corps’ own funds, totaling close to $20 million.

Our work grew in proportion to the wider response: in early 2019, as the virus continued to spread within rural territories in North Kivu, posing risk of transmission to larger urban areas, Mercy Corps implemented the Vision Ebola Zero (VISEZ) program to strengthen preparedness in the city of Goma.

After concerted advocacy efforts led to the ‘system-wide scale up’ of the Ebola response by the Ebola Response Coordination in July 2019, emphasizing community engagement, Mercy Corps’ Pamoya Tujikengele ku Ebola project worked in partnership with 40 local organizations to operate Ebola information centers in Butembo and Katwa.

Beginning shortly afterwards in August 2019, we began to scale up community WASH efforts in 18 communities, ultimately benefiting 141,500 people.

From October 2019, Mercy Corps led the Lutter contre Ebola Via l’Engagement de Communautés Redynamisées (LEVER) consortium which sought to improve community-based surveillance and preparedness through extensive engagement with community structures in 14 health zones. By the time the LEVER program concluded in January 2021, bringing to a close Mercy Corps’ Ebola portfolio of work, it had assisted a total of 658,916 people.

What We Learnt

From the outset it was clear that this outbreak was going to be uniquely challenging, even within the context of DRC’s long history of Ebola outbreaks. The conflict dynamics in Eastern DRC, the logistical challenges of operating in areas poorly served by road networks, and the reliance on transboundary trade for the region’s economy were all complicating factors for the response, which was also taking place in a region that had long been the focus of humanitarian assistance.

A multi-sectoral approach

From early on, Mercy Corps was an advocate for joined-up approaches that went beyond medical or health actions, recognizing that if the government and humanitarian community did not also try to tackle wider social and economic challenges then the response would struggle to gain traction.

Addressing the roots of this lack of trust on the part of communities required a multi-sectoral approach, including community mobilization campaigns and actions that directly engage community members and trusted leaders in ongoing conversations about the risks posed by the Ebola outbreak and which support the implementation of locally-owned actions to prevent the spread of the disease.

Community engagement at the forefront

At the center of this multisectoral approach was a robust approach to community engagement, a lesson seemingly learned and then forgotten after successive disease outbreaks. The early Kivu Ebola outbreak response was largely top-down, encountering a lack of trust on the part of affected populations that was often characterized as “community resistance.” It wasn’t until the system-wide scale up of the response in mid-2019 that this began to change.

The key principles of our approach to community engagement were as follows:

- Diversification of our community-based partners to work with over 5,000 Care Group volunteers, 59 local organizations, and support more than 1,300 community action cells.

- Involvement of community leaders and pre-existing groups to build on trusted community structures and bolster what was already working.

- Putting in place two-way communication mechanisms to build trust.

- Focusing on “wraparound” support to communities - responding to expressed needs in a durable way that looked not just at health but other sectors.

- Facilitating access to information, through hotlines, radio, information centers, and neighborhood networks to foster behavior change.

The success of efforts to better engage local actors was striking. For example, when we partnered with 40 local organizations in Butembo and Katwa to run Ebola information centers that allowed members of the community to ask questions, give feedback, and discuss perceptions around the disease and response, we witnessed a drastic improvement of public confidence in the response, from 18% in June 2019 to 91% in April 2020.

Tracking and tackling misinformation

Misinformation, rumors and myths swirled around the tenth Ebola outbreak, clouding the ability of responders to target assistance and further undermining trust in the government-led response. Mercy Corps and other actors struggled with how to identify, track, and effectively respond to misinformation as the response evolved.

One of the tools at our disposal is our Congo Humanitarian Analysis Team (C-HAT), which worked with partners to develop a Community Perceptions Tracker. Through field-based reporting and the use of a hotline, the CHAT led the collection of information on perceptions, questions and feedback at the community level, analyzing and packaging these data to share with implementers and the wider coordination effort. This tracker was eventually adapted to also track misperceptions about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Read more: See reports from our Community Perceptions Tracker stored here.

Improved messaging for behavior change

Identifying information gaps and misconceptions that need tackling is useful, but on its own won’t lead to change unless accompanied by targeted, effective messaging designed to influence behavior shifts.

For example, images must be accurate, appropriate to local norms, and respond to people’s questions: for instance, posters used prominently during the beginning of the response showed images of people bleeding, vomiting, crying, or having diarrhea. However, in most cases, Ebola disease does not lead to major hemorrhage and instead presents with malaria-like symptoms. The messaging around symptoms was therefore confusing and limited the up-take of messaging around other issues.

- Read more: We partnered with Translators Without Borders, who conducted research during the outbreak that highlighted best practices and what to avoid in terms of communication. Reports from that effort are available here.

Investing in infrastructure for sustained impact

As a leader in sustainable water and sanitation solutions in Eastern DRC, Mercy Corps recognized the value of investing in infrastructure that would enable affected populations to better help prevent the spread of the disease.

Early in the response, our EMPACTE project provided an innovative solution in linking the medical response on IPC to strengthening WASH and community engagement services. Mercy Corps exclusively built new WASH infrastructure with semi-durable materials, providing cleaning and maintenance kits, and incentivizing healthcare workers with capacity building through training on the application of IPC measures and the appropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Over the course of four evaluations carried out in 15 health centers over five months, the average score of health facilities increased from 13.6% in the first assessment to 91.5% in the fourth and last assessment.

Interested in learning more? Download the full LEVER lessons learned document here.

What Needs To Happen Now?

As the world continues to confront the global COVID-19 pandemic, and as Eastern DRC faces a range of deeply rooted challenges, the lessons learned from the tenth Ebola outbreak remain as pertinent as ever.

- Engaging communities and identifying local solutions: Failing to meaningfully engage participating communities in tackling any development or humanitarian challenge - whether a health epidemic, food insecurity crisis, or cyclical conflict - will render the response less efficient, less effective and less sustainable. Local populations must be at the center of our work, no matter the sector.

- Tracking perceptions and tailoring messaging to counter misinformation: In an age where false information spreads more widely and deeply than ever before, development actors need to pilot innovative solutions to track and counter rumors, myths, and disinformation campaigns through messaging that is tailored to recipient communities.

- Developing multisectoral solutions for Eastern DRC: The Ebola outbreak was ultimately a symptom of wider challenges that continue to undermine the prospects for durable peace in Eastern Congo. Development programs need to take joined-up approaches, in line with the Triple Nexus, to improve social cohesion, governance and economic opportunities at the systems level, or risk remaining superficial in their impacts.

How Mercy Corps’ response was covered in local and international media:

- The New Humanitarian, ‘We can’t stop Congo’s Ebola outbreak until communities lead the response’ (August 2019)

- Radio Moto, ‘Nord-Kivu : l’ONG Mercy Corps remet des ouvrages d’accès à l’eau potable aux populations de la zone de santé de Musienene’ (December 2020)

- Actualité.cd, ‘RDC : grâce aux feedbacks communautaires, Mercy Corps a aidé à changer la perception dans l’éradication d’Ebola dans l’Est’ (December 2020)

- Actualité.cd, ‘RDC : au-delà d’Ebola, le projet LEVER de Mercy Corps a aussi aidé les communautés à se débarrasser d’autres maladies à potentiel épidémique’ (December 2020)

- Actualité.cd, ‘RDC: projet LEVER de Mercy Corps, l'exemple d'une approche partenariale innovante pour stopper des épidémies le plus rapidement possible’ (January 2021)